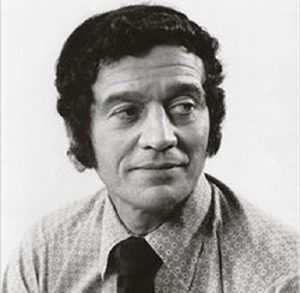

Anatole Broyard

*Anatole Broyard was born on this date in 1920. He was a Black writer and literary critic. Anatole Paul Broyard was born in New Orleans, Louisiana, into a Black Creole family established as free people of color before the American Civil War. The first Broyard recorded in Louisiana was a French colonist in the mid-eighteenth century.

He was the son of Paul Anatole Broyard, a carpenter and construction worker, and his wife, Edna Miller, neither of whom had finished elementary school. Broyard was the second of three children; two years older, he and his sister Lorraine were light-skinned with European features. Their younger sister, Shirley, had darker skin and African features. When he was a child, his family moved to New York City as part of the Great Migration; His father thought there were more work opportunities. They lived in a working-class and racially diverse community in Brooklyn. Having grown up in the French Quarter's Creole community, Broyard felt he had little in common with the urban Blacks of Brooklyn. He saw his parents "pass" as white to get work, as his father found the carpenters union racially discriminatory.

By high school, the young Broyard had become interested in artistic and cultural life; his sister Shirley said he was the only one in the family with such interests. While growing up in Brooklyn, where his family had moved, he was ostracized by both white and black kids. The Black kids picked on him because he looked white, and the white kids rejected him because they knew his family was Black. He'd come home from school with his jacket torn, and his parents wouldn't ask what happened. As an adult, he didn't tell his family about his racial background because he wanted to spare his children from going through what he did. Broyard had some stories accepted for publication in the 1940s. He began studying at Brooklyn College before the U.S. entered World War II.

The armed services were segregated when he enlisted in the army, and no Blacks were officers. He was accepted as white at enlistment and took that opportunity to enter and complete officers’ school. During his service, he was promoted to the rank of captain. Broyard first married Aida Sanchez, a light-skinned, Black Puerto Rican woman; they had a daughter, Gala. They divorced after Broyard returned from military service in World War II.

During the 1940s, Broyard published stories in Modern Writing, Discovery, and New World Writing, three leading pocket-book format "little magazines." He also contributed articles and essays to periodicals such as Partisan Review, Commentary, Neurotica, and New Directions Publishing. His stories were included in two anthologies of fiction widely associated with the Beat writers, but Broyard did not identify with them. He did not identify with or champion Black political causes. Because of his artistic ambition, he never acknowledged his blackness in some circumstances. On the other hand, Margaret Harrell wrote that she and other acquaintances were casually told that he was a writer and Black before meeting him, and not in the sense of having to keep it a secret.

He often was said to be working on a novel but never published one. After the 1950s, Broyard taught creative writing at The New School, New York University, and Columbia University, in addition to his regular book reviewing. That he was partially black was well known in the Greenwich Village literary and art community from the early 1960s. For nearly fifteen years, Broyard wrote daily book reviews for The New York Times. John Leonard's editor said, "A good book review is an act of seduction, and when he [Broyard] did it, there was no one better." In 1961, at 40, Broyard married again to Alexandra (Sandy) Nelson, a modern dancer and younger white-American woman (of Norwegian) ancestry. He was indirect about his family, but she learned about him. They had two children: son Todd, born in 1964, and daughter Bliss, born in 1966. The Broyards raised their children as whites in suburban Connecticut. When they had grown into young adults, his wife urged him to tell them about his family (and theirs), but he never did.

In the late 1970s, Broyard started publishing brief personal essays in the Times, which many considered among his best work. These were collected in Men, Women, and Anti-Climaxes, published in 1980. In 1984, he was given a column in the Book Review, for which he also worked as an editor. He was among those considered "gatekeepers" in the New York literary world, whose positive opinions were critical to a writer's success. Shortly before he died, Broyard wrote a statement others later took to represent his views. In explaining why he so missed his friend, the writer Milton Klonsky, with whom he used to talk every day, he said that after Milton died, "No one talked to me as an equal."

Although critics framed the issue of his identity as one of race, Broyard wanted personal equality and acceptance: he wanted neither to be talked down to nor looked up to, as he believed either masked the true human being. His wife told their children of their father's secret before his death. AnatoleBroyard died in October 1990 of prostate cancer, diagnosed in 1989. His The New York Times obituary did not mention his first wife and child.