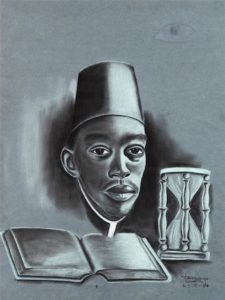

Wilmer Jennings

*The birth of Wilmer Jennings is celebrated on this date in 1910. was a Black printmaker, artist, and jeweler.

Wilmer Angier Jennings was born in Atlanta, Georgia. While attending Morehouse College in Atlanta, Georgia, Jennings studied under the artist Hale Woodruff, who introduced him to the principles of modernism. Under the Graphic Arts Division of the Works Progress Association (WPA) in 1934, they worked together on two notable murals that reflected on the African American experience: The Negro in Modern American Life: Agriculture and Rural Life, Literature, Music and Art and the second, titled The Dream. The first of the two was displayed in the David T. Howard School in Atlanta, Georgia, while the second was showcased at the School of Social Work at Atlanta University. However, both were destroyed.

During that stay in Atlanta, Jennings learned the creative production that contributed to community murals. Woodruff already had an unconventional relationship with his students, and he opposed the typical teacher role. Because of that, Jennings formed a personal friendship with Woodruff, who he called "Count" as a playful title rather than calling him Hale. Regarding this relationship, art historian Winifred L. Stoelting quoted Woodruff saying: "I remember they wanted to call me 'Hale' and I was reluctant for them to do that, but Wilmer Jennings always called me 'Count,' a kind of a warm title. I always appreciated it because he needed [to] and wanted this kind of relationship that developed between us."

Jennings continued to work with Woodruff throughout his early career and was able to exhibit his oil painting, Rendezvous, 1942, in the First Atlanta University Annual Exhibition of Works by Negro Artists, an exhibition that Woodruff organized. After graduating from Morehouse College, Jennings moved to New England to attend the Rhode Island School of Design. There, he was hired by the WPA, where he created works that represented the economic hardships of Blacks during the Depression. During this time, he mostly used wood engraving and linocut relief processes. Wood engraving uses a dense block for processing, so Jennings created thin lines that displayed subtle detail. His Still Life, 1937, used this technique to create a shadowy quality. However, Linocut uses a softer linoleum block that cannot be processed similarly. Jennings’ Statuette, 1937, emphasized contrast by creating free bold lines.

The Rhode Island WPA hired him to create wood-engraved prints that explored themes of economic and social hardships experienced by Blacks. Jennings' work also included Southern themes inspired by oral folklore traditions. During his later years, Jennings studied jewelry design, which prompted him to develop new jewelry manufacturing methods. His African roots influenced Jennings and he began incorporating African sculpture into his works. Still Life, 1937, and Statuette, 1937, include images of an African Fang sculpture and the objects found in Gabon working-class households. Jennings enjoyed reading and was influenced by Zora Neale Hurston and by the poetry of Sterling Brown.

Jennings's wood engraving Just Plain Ornery, 1938, represents the humor associated with folklore by presenting the stubborn mule and mule races. After moving to Providence, Rhode Island, in the mid-1930s, Jennings represented the effect of urban development on the black community in some of his works. His prints included images of ferry boats, oil industry sites, racetracks, and the transformation of residential areas.

In addition to establishing himself as a printmaker, Jennings supported his family by working as a jewelry designer. From 1943 until his death, Jennings developed a series of new techniques that benefited the company for which he worked, the Imperial Pearl Company. As a head jewelry designer and chief model maker, Jennings reduced the thickness of castings by casting with rubber molds. He taught himself how to cast precious metals using a lost wax method. He also developed a method to color glass beads using alabaster and crushed colored glass, which created a new jade color. His adoption of centrifugal casting instead of injection-molded pieces also reduced costs. After injuring his right hand in 1957, Jennings began to train himself to draw and paint left-handed, which he continued to do until his death. The subjects of his later work included landscape and social realist scenes of his community.

Wilmer Jennings died in 1990. Jennings’ daughter Corrine Jennings is the director of Kenkeleba House, Inc. in New York City, dedicated to showcasing the work of underrepresented African artists. Kenkeleba House was founded in 1974 by Jennings, Joe Overstreet, and Samuel C. Floyd.

To become a jeweler, seamstress, textile/fine artist

To be an Artist