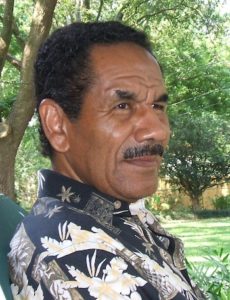

Wilbert Rideau

*Wilbert Rideau was born on this date in 1942. He is a former Black death row inmate, author, and prison journalist.

From Lawtell, Louisiana, when he was six, his family moved to Lake Charles near the Texas border. Rideau grew up in the Jim Crow South; he attended the all-black Second Ward Elementary School. He loved science and dreamed of becoming a spaceman like his high-flying comic book hero, Flash Gordon Poor even by the standards of the Black community, Rideau recalls that before the free lunch program was initiated, he frequently had nothing to take to school for lunch but a cold sweet potato which, he says, he often threw away out of embarrassment.

When his parents divorced, everything went further downhill. The family's poverty intensified. Wilbert's inability to fit in with his classmates grew worse. After transferring to the W.O. Boston Colored High School in eighth grade, he began playing hooky from school, shooting dice on the unkempt and vandalized tombs in the overgrown cemetery across the street from his house. There, he bought friendships with other truants in the form of cigarettes.

At age 13, he found a job at a local grocery where he said he was 16 and had quit school. The trade-off was payment at less than minimum wage, which reinforced Rideau's ever-growing sense that fairness was not to be expected from white people. Eventually, he stopped going to school altogether. A series of low-paying, menial jobs was his passport to the pool hall and the gin joints, where he hated his life, which dead-ended at a broom in the daytime, and in a barroom at night.

At 19, Rideau was convicted of murder and sentenced to death; in prison, he began to read insatiably, both the religious literature allowed to prisoners then, as well as books smuggled to him by the white deputies and prison guards whose job it was to watch him. On Death Row, Wilbert began to write, penning in longhand a book-length analysis of criminality that he expected to be found after his execution. He also wrote a manuscript for a novel about a young white boy finding his way in the segregated South. He struck up a correspondence with Clover Swann, a young editor at a New York publishing house, who tutored him through the mail in the craft of writing.

In 1973, a year after the Furman v. Georgia ruling, the United States Supreme Court declared the death penalty unconstitutional, and Rideau was released into the general population at Angola. When his request to be assigned to the all-white Angolite publication staff was refused, he rounded up an all-Black staff and started The Lifer, a publication aimed at men serving life sentences. In 1974, he began writing a weekly column, "The Jungle," for a chain of Black newspapers in the South.

When the federal court in 1975 ordered wholesale reforms at Angola and ordered integration of the inmates, among other reforms, outgoing warden C. Murray Henderson hurriedly installed Rideau as editor of the Angolite. C. Paul Phelps, the incoming interim warden, who became Secretary of Corrections, ratified that choice in 1976 and struck a deal with Rideau that the Angolite would operate under the same standards of freedom and responsibility that applied to journalists in the "free world." He could print whatever he could prove.

Rideau brought his Lifer co-editor, Tommy Mason, to the Angolite, and the magazine began winning national awards the next year. With a series of writers, editors, and artists hand-picked by Rideau, the Angolite and its staff won some of journalism's most prestigious awards and high praise from the free-world media. Co-editor Ron Wikberg's article, "The Horror Show," was widely credited as instrumental in shifting Louisiana’s method of execution from the flesh-burning electric chair to the more humane lethal injection.

By the late 70s, Rideau had become a sought-after speaker on criminal justice and journalism issues, lecturing at universities and appearing on local and national radio and television programs. In 1984, in one of many Nightline appearances, he shared the electronic stage with Chief Justice Warren Burger of the United States Supreme Court. In 1989 and 1990, he flew to Washington, D.C., to address the annual convention of the American Society of Newspaper Editors.

In 1991, Rideau collaborated with the University of Louisiana to produce Life Sentences criminal justice textbook. The following year, ABC-TV’s World News Tonight jointly named Rideau and his colleagues “Person of the Week.” Also during that time, Rideau became a correspondent for National Public Radio's Fresh Air and embarked on a series of collaborations with "free-world" partners that netted prestigious awards: "Tossing Away the Keys," a 1990 NPR documentary, won a Livingston Award, "In for Life," a short documentary done in 1994 won a CINE Golden Eagle, then Final Judgment: The Execution of Antonio James in 1996 for the Discovery Channel, won both a CINE Golden Eagle and the Thurgood Marshall Award; and The Farm, in 1998, yielded an Oscar nomination for the film and a Tree of Life Award for Rideau.

Rideau remains editor of the Angolite. He is currently working on a major research project in his spare time. Since his 2005 trial and release after 44 years in prison, Wilbert Rideau has devoted himself to educating people about the realities of the world behind bars. He has spoken widely, including at Continuing Legal Education training sessions and legal conferences. His autobiography, In the Place of Justice: A Story of Punishment and Deliverance, was published in April 2010.