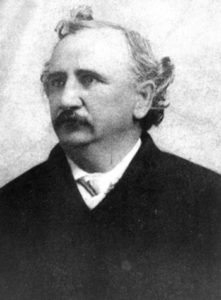

Thomas Miller

This date marks the birth of Thomas Ezekiel Miller in 1849. He was a Black politician, lawyer, and educator elected to the South Carolina Congress and served from 1889 to 1891.

Miller was born in Ferrebeeville, South Carolina, named after his adoptive mother's slave master. His origins were unclear, although he apparently had a majority European heritage. The historians Eric Foner and Stephen Middleton found that his mother was a Mulatto daughter of Judge Thomas Heyward, Jr., a signer of the Declaration of Independence, and his father a wealthy young white man, whose family rejected their relationship. They forced him to give up his son for adoption. He was adopted by former slaves Richard and Mary Ferrebee Miller, who were freed by 1850.

In 1872, Miller was the school commissioner of Beaufort County, South Carolina. He subsequently moved to Columbia and studied law at the then-recently integrated the University of South Carolina. He also studied with the state solicitor and state Supreme Court justice. He was admitted to the bar in December 1875. Miller was a member of the state general assembly from 1874 to 1880, when he went to the state senate. That same year he was nominated for lieutenant governor but did not enter the race because the South Carolina Republican Party declined to put forward a state ticket. Miller returned to the state house of representatives in 1877. He served on the Republican State executive committee from 1878 to 1880 and was state party chairman in 1884.

In 1888, Miller ran for Congress from the Seventh District against Democratic candidate William Elliott, who was declared the winner. Miller contested the election, alleging that many Black voters who were registered correctly had not been permitted to cast their ballots. The House Committee on Elections eventually ruled in his favor, and Miller was sworn into the Fifty-first Congress on September 24, 1890. He took a seat on the Committee on the Library of Congress but was involved in two lengthy contested election cases that diverted his attention from legislative business.

In 1890, Miller ran for reelection and was the apparent victor over Elliott and independent Republican E.W. Brayton. Elliott insisted that the vote count was fraudulent and challenged the results. The South Carolina Supreme Court ruled that Elliott was entitled to the seat because the color and size of Miller's ballots were illegal. When the Fifty-second Congress assembled on December 7, 1891, Miller asked the House to declare him the winner. Still, most of the Elections Committee in February 1893 gave the seat to Elliott. By the time of the committee's ruling, Miller had been defeated for the Republican nomination by George W. Murray, who was elected to represent the Seventh District in the Fifty-third Congress.

Miller had lost his reelection bid to the Fifty-third Congress and was challenging Elliott's election to the Fifty-second when he spoke to the House in January 1891 on Representative Henry Cabot Lodge's bill authorizing the government to oversee federal elections and protect voters from violence and intimidation. Miller ignored threats that his remarks would endanger his chances of being seated in the next Congress and urged the Senate to follow the House and take favorable action on Lodge's proposal. He rejected Democratic claims that the election law was a force bill designed to perpetuate misrule by incompetent and corrupt Blacks.

On February 14, 1891, Miller delivered a major address in reply to a speech by Senator Alfred H. Colquitt of Georgia, who blamed Blacks for retarding the South's economic development. Miller replied that the Colquitt speech was an offensive mixture of theology and political economy that contained groundless slanders against Blacks. Miller declared that White southerners were chiefly responsible for the region’s economic problems because they were motivated by bigotry and vengeful in denying Blacks full citizenship rights. From 1894 to 1896, Miller served once more in the state house of representatives.

He was a delegate in 1895 to the state constitutional convention that disenfranchised most Blacks by approving election laws requiring, among other things, that voters read and write any part of the South Carolina constitution or prove that they owned at least $300 in the property. Miller, Congressman George Murray, and former Representative Robert Smalls spoke against these and other racist provisions, but their efforts were unsuccessful. After Claflin College in Orangeburg lost its federal funding, Miller helped establish the State Negro College (now South Carolina State College) in the same town.

In March 1896, he became that college’s president and worked to promote the employment of Black teachers in Black public schools. He was forced to resign in 1911 by Governor Coleman L. Blease, whom he had opposed in the previous year’s election. Miller retired from active pursuits and lived in Charleston until 1923, when he moved to Philadelphia.

He was, except John R. Lynch of Mississippi, the last survivor of the post-Civil War generation of Black representatives. Thomas Ezekiel Miller returned to Charleston in 1934 and died there on April 8, 1938.

Black Americans in Congress 1870-1989.

Bruce A. Ragsdale & Joel D. Treese

U.S. Government Printing Office

Raymond W. Smock, historian and director 1990

E185.96.R25