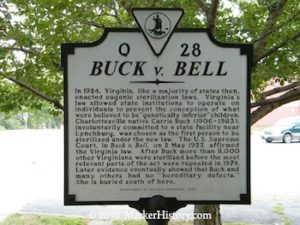

Virginia Plaque

*On this date in 1927, the Supreme Court ruled Buck v. Bell, 274 U.S. 200. This episode followed the Virginia Racial Integrity Act of 1924 and channeled race into an unmonitored deciding factor of sterilization in America.

Buck v. Bell was the United States Supreme Court ruling that a state statute permitting compulsory sterilization of the unfit, including the intellectually disabled, "for the protection and health of the state" did not violate the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. As of 2019, the Supreme Court has never expressly overturned Buck v. Bell. Written by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., the litigation made its way through the court system. Dr. Albert Sidney Priddy, superintendent of the Virginia State Colony for Epileptics and Feebleminded, filed a petition to his Board of Directors to sterilize Carrie Buck, an 18-year-old patient at his institution which he claimed had a mental age of 9. Dr. John Hendren Bell took up the case.

The Board of Directors issued an order for the sterilization of Buck, and her guardian appealed the case to the Circuit Court of Amherst County, which sustained the decision of the Board. The case then moved to the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia. The appellate court sustained the sterilization law as compliant with state and federal constitutions, and it then went to the United States Supreme Court. Buck and her guardian contended that the due process clause guarantees all adults the right to procreate, which was being violated. They also argued that the Equal Protection Clause in the 14th Amendment was being violated since not all similarly situated people were being treated the same. The sterilization law was only for the "feeble-minded" at certain state institutions and did not mention other state institutions or those who were not in an institution.

In an 8–1 decision, the Court accepted that Buck, her mother, and her daughter were "feeble-minded" and "promiscuous" and that it was in the state's interest to have her sterilized. Carrie Buck was operated upon, receiving a compulsory salpingectomy (tubal ligation). She was later paroled from the institution as a domestic worker to a family in Bland, Virginia. She was an avid reader until she died in 1983. Her daughter Vivian had been pronounced "feeble-minded" after a cursory examination by ERO field worker Dr. Arthur Estabrook. According to his report, Vivian "showed backwardness," thus the "three generations" of the majority opinion. It is worth noting that the child did very well in school for the two years she attended (she died of complications from measles in 1932), even being listed on her honor roll in April 1931.

Historian Paul A. Lombardo argued in 1985 that Buck was not "feeble-minded" at all but had been put away to hide her rape, perpetrated by the nephew of her adoptive mother. He also asserted that Buck's lawyer, Irving Whitehead, poorly argued her case, failed to call important witnesses, and was remarked by commentators to often not know what side he was on. It is now thought this was not because of incompetence but deliberate. The ruling legitimized Virginia's sterilization procedures for 50 years until they were repealed in 1974.