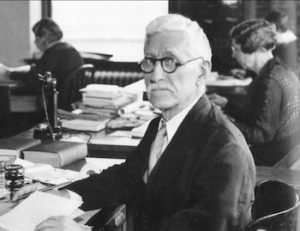

Walter A. Plecker

*Walter Plecker was born on this date in 1861. He was a white-American physician, public health advocate, and racial separatist.

Walter Ashby Plecker was born in Augusta County, Virginia, the son of a Confederate soldier and raised by a Black nanny. Sent to Staunton, Virginia, as a boy, he graduated from Hoover Military Academy in 1880 and obtained a medical degree from the University of Maryland in 1885. He was a devout Presbyterian, and throughout his life, he supported the denomination's fundamentalist Southern branch, funding missionaries who believed, like he later came to, that God destroyed Sodom and Gomorrah for racial intermixing.

Plecker moved to Hampton, Virginia, in 1892. Before his mother's death in 1915, he worked with women of all races and became known for his active interest in obstetrics and public health issues. Plecker educated midwives, invented a home incubator, and prescribed home remedies for infants. His techniques are credited with an almost 50% decline in birthing deaths for black mothers during that period. He became the public health officer for Elizabeth City County in 1902.

In 1912, Plecker became the first registrar of Virginia's newly created Bureau of Vital Statistics, a position he held until 1946. An avowed white supremacist and advocate of eugenics, he became a leader of the Anglo-Saxon Clubs of America in 1922. He wanted to prevent miscegenation or marriage between races and thought that a decreasing number of Mulattoes, as classified in the census, meant that more were passing as white. With the help of John Powell and Earnest Sevier Cox, Plecker drafted, and the state legislature passed the "Racial Integrity Act of 1924". It recognized only two races, "white" and "colored" (black).

It essentially incorporated the one-drop rule, classifying as "colored" any individual with any African ancestry. This went beyond existing law, which classified persons as white with one-sixteenth (equivalent to one great-great-grandparent) or less Black ancestry. Plecker particularly resented Negroes who passed as Indians and came to firmly believe that the state's Native Americans had been "mongrelized" with its African American population. After the American Civil War, Native Americans from all over the country had been brought to the Hampton area to be educated with Blacks, and some had married. However, the Indian school closed as racial discrimination against Indians, and this eugenics movement grew.

He refused to recognize that many mixed-race Virginia Native Americans had maintained their culture and identity as Indians over the centuries despite economic assimilation. Plecker ordered state agencies to reclassify most citizens who claimed Native American identity as "colored," although many Virginia Indians had continued in their tribal practices and communities. Church records, for instance, continued to identify them as Indians. Specifically, Plecker ordered state agencies to reclassify certain families he identified by surname, as he had decided they were trying to pass and evade segregation.

He also lobbied the US Census Bureau to drop the category of "mulatto" in the 1930 and later censuses. This deprived mixed-race people of recognizing their identity and contributed to a binary culture of hypodescent. Mixed-race persons were often classified as the group with lower social status. Not until the 21st century did the census allow individuals to indicate more than one race or ethnic group in self-identification. Plecker was hit by a car crossing Richmond Street and died on August 2, 1947. He is buried beside his wife in Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond, VA. In 1967, the United States Supreme Court invalidated the law in Loving v. Virginia. His ordering state agencies to reclassify certain families he identified by surname remained legal in the South until federal legislation in the 1960s.

Plecker's racial policies continue to cause problems for descendants of what is now sometimes called the First Virginians (FFV). Members of eight Virginia-recognized tribes struggle to achieve federal recognition because they cannot prove their continuity of heritage through historical documentation, as federal laws require. Encountering European Americans first during the colonial period, the tribes had treaties mostly with the King of England rather than the United States government. His policies destroyed and altered records that individuals and families need to show cultural continuity as Indians. In 2007, the House of Representatives passed a law to recognize the Virginia tribes at the Federal level, but the Senate has yet to pass it into law.