The Port Chicago Disaster occurred on this date in 1944, an explosion where over 60 percent of the casualties were Black enlisted men.

During World War II, the Naval Ammunition Depot at Port Chicago, California, was one of the ammunition sources for the Pacific Theater. Port Chicago is located about 30 miles northeast of Oakland and San Francisco. Vallejo's Mare Island was not far away but a major naval base with ammunition depots. After World War I, the Navy tried to exclude Blacks, replacing their ranks with Filipinos. In 1932, the Navy again recruited Blacks, but they were limited in numbers and confined to menial tasks, primarily as kitchen helpers. There were no Black officers. In 1942, the Navy reluctantly accepted Blacks for general service except in segregated units that did not include sea duty.

Building the Port Chicago depot was authorized on December 9, 1941, just two days after Pearl Harbor. Operations began in November 1942. The site was a shipyard during World War I, served by the Santa Fe, Southern Pacific, and Western Pacific railways.

At the time of the disaster, at Port Chicago, there were 1,400 Black enlisted men, 71 officers, 106 marine guards, and 230 civilian employees. The loading went on 24 hours a day. The men moved the ammunition hand-to-hand, on hand trucks or carts, or rolled larger bombs down a ramp from the boxcars, which were right on the pier and placed them into cargo netting, which they spread out on the pier.

Most of the ammunition arrived by train from Hawthorne, Nevada, where it was made and held in boxcars "parked" between protective concrete barriers. The train was moved onto the pier that accommodated two ships when needed. About a mile from the pier were barracks that housed the Black ammunition handlers. On that evening, two ships were at the Port north of San Francisco.

After four days of loading, the Liberty ship, SS E.A. Bryan, had about 4,600 tons of ammunition and explosives on board, with 98 Black enlisted men working. Also involved was the SS Quinault Victory, loaded by about 100 Black men for its maiden voyage. On board were 36 crew and 17 Armed Guards. A Coast Guard fire barge was also anchored at the pier. In addition to 430 tons of bombs waiting to be loaded, the pier held a locomotive and 16 boxcars with a crew of three civilians and a marine sentry.

The ammunition included small caliber bullets, incendiary bombs, fragmentation bombs, depth charges, and bombs up to 2,000 pounds. The ship’s booms lowered the cargo nets into a hatch, packed layer-by-layer and secured with scrap wood. Neither the officers nor the men received any training in handling ammunition. There was enormous pressure to speed up the loading, and officers bet on how much ammunition their unit would load in an 8-hour shift. The men were forced to speed up by threats of punishment even though it was dangerous work.

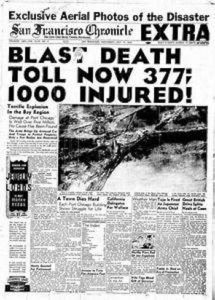

At 10:18 that evening, the explosion happened; an Army Air Force plane flying at 9,000 feet saw pieces of white-hot metal, some as large as a house, fly straight up past them. The explosion was heard 200 miles away. The 1,200-foot-long wooden pier, the locomotive and boxcars, the SS E.A. Bryan, and 320 people (202 black enlisted men) on the pier were gone. All 67 crew and 30 Armed guards aboard the two ships died instantly. Of the 390 military and civilians injured, which included men in the barracks and townspeople, 233 were Black enlisted men. No identifiable pieces of the SS E.A. Bryan remained; 25,000,000 pounds of ship and ammunition were also gone.

No cause for the explosion was ever determined. The Black ammunition handlers, many of whom had quietly voiced safety concerns, feared loading ammunition again. Fifty enlisted Black men, including one with a broken arm, were tried for mutiny. The men stated they were willing to follow orders but were afraid to handle ammunition under unchanged circumstances. They stated they had never been ordered to load ammunition, only asked: "if they wanted to load ammunition." All 50 were found guilty of "mutiny" and sentenced to 15 years.

A review of the sentence reduced 40 men's sentences to 8 to 12 years. Joe Small, who acted as foreman for his group of loaders, and others willing to criticize the operation had their original sentences upheld. Thurgood Marshall of the NAACP appealed it, but was denied. In 1944, the Navy announced that Blacks at ammunition depots would be limited to 30 percent of the total.

In 1945, the Navy officially desegregated. In January 1946, the 50 "mutineers" were released from prison but had to remain in the Navy. They were sent to the South Pacific in small groups for a "probationary period" and gradually released. A proposal in Congress to award $5,000 to victims was reduced to $3,000 because most of the beneficiaries were Black.

The Navy eventually bought out the town of Port Chicago, and the depot was incorporated into the Concord Naval Weapons Station. Concord was a major shipping point for ammunition during the Vietnam War and the site of many anti-war demonstrations that continued into the 21st century.

Library of Congress

101 Independence Avenue S.E.

Washington D.C. 20540