St. Agnes, South Corlina

On this date, we celebrate Black Hospitals in America. Black hospitals have existed in three broad types: segregated, black-controlled, and demographically determined.

Segregated Black hospitals included facilities created by whites to serve Blacks exclusively, and they operated predominantly in the South. Black physicians, fraternal organizations, and churches founded Black-controlled facilities. Population changes led to demographically determined hospitals such as the Harlem Hospital. This facility evolved into institutional status because of the rise in the Black population surrounding the New York facility.

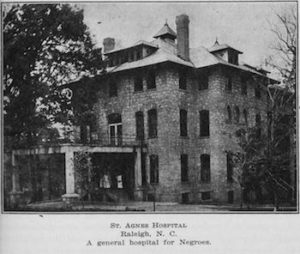

Until the rise of the American Civil Rights Movement, hospitals in the South and the North denied Blacks admission or accommodated them exclusively in segregated wards, usually in undesirable locations such as unheated attics and damp basements. The Georgia Infirmary, 1832, was the first segregated Black hospital. By the end of the nineteenth century, others had been founded, including Raleigh’s St. Agnes Hospital in 1896 and Atlanta’s MacVicar Infirmary in 1900. Some of their white founders expressed genuine paternalistic desire and interest to supply health care to Black people.

White self-interest was at work, too. The germ theory of disease, widely accepted then, acknowledged that “germs have no color line.” This theory required attention to the medical problems of African Americans, especially those who were close to whites in proximity. Soon, Blacks founded hospitals to meet the specific needs of the African American communities. Provident Hospital in Chicago, the first Black-controlled hospital in America, opened in 1891. Racism in Chicago prevented Black nurses and doctors from practicing, thus eliminating health care for black patients.

Other facilities opened up, including Tuskegee Institute and Nurse Training School in Alabama in 1892, Provident Hospital in Baltimore in 1894, Frederick Douglass Memorial Hospital and Training School in Philadelphia in 1895, and Wheatly Provident Hospital in Kansas City. These hubs of medical assistance for African Americans represented in part the institutionalization of Booker T. Washington’s political ideology, advancing racial uplift by improving the health status of Black people and by contributing to the Black professional class.

By 1919, roughly 118 segregated and Black controlled hospitals existed, three-fourths in the South. Most of them were small and not full-service units. They were unprepared to survive sweeping changes in scientific medicine, hospital technology, and standardization that had begun to take place at the time. This was the most critical condition of survival in historically Black hospitals between 1920 and 1945. In the late 19th century, a group of physicians associated with the National Negro Medical Association (NNMA), a Black medical society, and the National Hospital Association (NHA), a Black hospital organization, launched a reform movement to ensure the survival of these hospitals and the maintenance of professions for Blacks.

With added financial help from White philanthropists, their activities produced some improvements and preservations by World War II. However, this “Negro Hospital Renaissance” showed that by 1923, out of 200 Black hospitals, only six provided internships, and none had residency programs. In 1944, the number of hospitals increased to 124. The American Medical Association (AMA) approved nine of the facilities for internships and seven for residencies, with the quality of some being suspect. The AMA admitted that their decision was partly based on the need for some internship opportunities for Black doctors.

This attitude highlights the then-accepted practice of treating Black people in separate but unequal facilities. During the American Civil Rights Movement, the energies of the NMA, the NHA, and the NAACP focused on dismantling the “Negro medical ghetto” of which Black hospitals were a component. The protest between 1945 and 1965, poised toward integration in medicine, challenged the existence of the Historically Black hospital. Legal action was a key weapon in the desegregation of hospitals. With the Brown v. Kansas Board of Education precedent, Simkins v. Moses H. Cone Hospital proved pivotal in 1963. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibited racial discrimination in any program receiving federal assistance.

Because of these changes in healthcare considerations, Black hospitals now face an ironic dilemma. They now compete with hospitals that had once discriminated against Black patients and staff. Since 1965, African American physicians have gained access to the mainstream medical profession, and Black hospitals have become less and less important to their careers, affecting their importance to the Black middle-class patient. Consequently, the vulnerability of the black hospital has increased dramatically.

Historically, Black hospitals have had a significant impact on the lives of African Americans. They evolved out of critical need and as a symbol of pride and achievement within the Black community. They supplied medical care and professional opportunities for countless African Americans. They are now becoming non-essential to most Americans' lives and are on the verge of extinction.

The Encyclopedia of African American Heritage

by Susan Altman

Copyright 1997, Facts on File, Inc. New York

ISBN 0-8160-3289-0