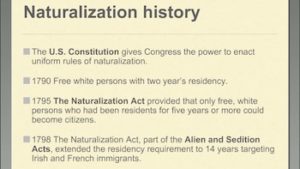

*On this date, in 1790, the Naturalization Act of 1790 was passed. This law of the United States Congress set the first uniform rules for granting United States citizenship by naturalization.

The law limited naturalization to "free white person[s] ... of good character". It excluded Native Americans, indentured servants, Black slaves, free Blacks, and later Asians, although free Blacks were allowed citizenship at the state level in several states. The Act was modeled on the Plantation Act of 1740 concerning time, oath of allegiance, the process of swearing before a judge, etc., and followed the theme of the Articles of Confederation.

There was a two-year residency requirement in the United States and one year in the state of residence before an alien would apply for citizenship by filing a Petition for Naturalization with "any common law court of record" having jurisdiction over his residence. Once convinced of the applicant's “good character,” the court would administer an oath of allegiance to support the Constitution of the United States. The applicant's children to the age of 21 would also be naturalized. The court clerk was to record these proceedings, and "thereupon such person shall be considered as a citizen of the United States." The Act also provided that children born abroad when both parents are U.S. citizens "shall be considered as natural born citizens," but specified that the right of citizenship did "not descend to persons whose fathers have never been resident in the United States."

This act was the only US statute ever to use the term "natural born citizen" found in the US Constitution in relation to the requirements for a person to serve as president or vice president. The term was removed by the Naturalization Act of 1795. Though the Act did not specifically preclude women from citizenship, the common law practice of coverture had been absorbed into the United States' legal system. Under this practice, the physical body of a married woman, thus any rights to her person or property, was controlled by her husband. A woman's loyalty to her husband was considered above her obligation to the state. Jurisprudence on domestic relations held that infants, slaves, and women should be excluded from participation in public life and conducting business because they lacked discernment, the right to free will and property, and there was a need to prevent moral depravity and conflicts of loyalty.

The Naturalization Act of 1795 repealed and superseded the 1790 Act. The 1795 Act extended the residence requirement to five years and added that a prospective applicant must give notice of the application of three years. The Naturalization Act of 1798 extended the residency requirement to 14 years and the notice period to five years. The 1798 Act was repealed by the Naturalization Law of 1802, restoring the residency and notice requirements of the 1795 Act. From the adoption of the Naturalization Law of 1804, women's access to citizenship was increasingly tied to their state of marriage.

By the end of the nineteenth century, the overriding consideration to determine a women's citizenship or ability to naturalize was her marital status. From 1907, a woman's nationality entirely depended on whether or not she was married. The Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek, ratified by the US Congress in 1831, allowed those Choctaw Indians who chose to remain in Mississippi to gain recognition as US citizens, the first major non-European ethnic group to become entitled to US citizenship. Major changes in citizenship rules were made in the 19th century following the American Civil War.