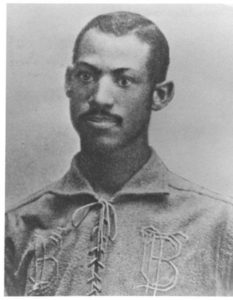

Moses Fleetwood Walker

*Moses Walker was born on this date in 1856. He was a Black professional baseball player and businessman. Moses Fleetwood Walker was born in Mount Pleasant, Ohio. Walker’s parents were Moses W. Walker and Caroline O' Harra.

When Walker was three years old, the family moved 20 miles northeast to Steubenville, where his father became one of the first black physicians of Ohio and later a minister of the Methodist Episcopal Church. Walker and his younger brother Weldy attended Steubenville High School in the early 1870s, just as the community passed legislation for racial integration. Walker enrolled at Oberlin College in 1878, majoring in philosophy and the arts.

At Oberlin, Walker proved himself to be an excellent student, especially in mechanics and rhetoric, but by his sophomore year, he became the prep team's catcher and leadoff hitter. Walker gained attention for his ball handling and ability to hit long home runs. In 1881, Oberlin lifted their ban on off-campus competition.

Walker played on the baseball club's first inter-collegiate team. Walker's performance in the season finale persuaded the University of Michigan to recruit him. Walker's girlfriend, Arbella Taylor, was Accompanying him, whom he married a year later. Michigan's baseball club had been weakest behind the plate; with Walker, the team performed well, finishing with a 10–3 record in 1882. He mostly hit second in the lineup and is credited with a .308 average. In mid-1883, Walker left his studies at Michigan and was signed to his first professional baseball contract with the minor league Toledo Blue Stockings, a Northwestern League team.

Walker hit in decent numbers, recording a .251 BA; he became revered for his play behind the plate and his durability during an era where catchers wore little to no protective equipment. He played in 60 of Toledo's 84 games during their championship season. At the core of the team's success, one sportswriter at Sporting Life pointed out, were Walker and pitcher Hank O'Day, which he considered “one of the most remarkable batteries in the country.”

Walker's entrance into professional baseball caused immediate friction in the league. Before he had the opportunity to appear in a game, the executive committee of the Northwestern League debated a motion proposed by the Peoria, Illinois, club representative that would prohibit all colored ball players from entering the league. The Blue Stockings' successful season in the Northwestern League prompted the team to transfer to the American Association, a major league organization, in 1884.

Walker's first appearance as a major league ballplayer was an away game against the Louisville Eclipse on May 1, 1884; he went hitless in three at-bats and committed four errors in a 5–1 loss. Throughout the 1884 season, Walker regularly caught for ace pitcher Tony Mullane. Mullane. Walker's year was plagued with injuries, limiting him to 42 games in a 104-game season. He had a .263 BA for the season, which was top three in the league, but Toledo finished eighth in the pennant race.

The team was also troubled by numerous injuries: circumstances led to Walker's brother, Weldy, joining the Blue Stockings for six games in the outfield. The Blue Stockings released Walker on September 22, 1884. During the offseason, Walker took a position as a mail clerk but returned to baseball in 1885, playing in the Western League for 18 games. In the second half of 1885, he joined the baseball club in Waterbury for ten games.

When the season ended, Walker reunited with Weldy in Cleveland to assume the proprietorship of the LeGrande House, an opera theater and hotel. Walker returned to Waterbury in 1886 when the team joined the more competitive Eastern League. Despite a lackluster season for Waterbury, Walker was offered a position with the defending champion Newark Little Giants, an International League team. Together with pitcher George Stovey, Walker formed half of the first Black battery in organized baseball. Walker followed Newark's manager Charlie Hackett to the Syracuse Stars in 1888.

On August 23, 1889, Walker was released from the team; he was the last black to play in the International League until Jackie Robinson. Walker stayed in Syracuse after the Stars released him, returning to a position in the postal service. Around this time, Walker designed the first of his four patented inventions, Walker invested in the design with hopes it would be in great demand, but the shell never garnered enough interest.

On April 9, 1891, Walker was involved in an altercation outside a saloon with a group of four white men exchanging racial insults. Walker responded by fatally stabbing Murray with a pocketknife. A compliant Walker surrendered to police, claiming self-defense, but was charged with second-degree murder (lowered from first-degree murder. Walker was found not guilty by an all-white jury, much to the delight of spectators in the courthouse. He returned to Steubenville to work for the postal service again, handling letters for the Cleveland and Pittsburgh Railroad.

On June 12, 1895, his wife Arabella died of cancer at 32 years old; he remarried three years later to Ednah Mason, another former Oberlin student. The same year, Walker was found guilty of mail robbery and was sentenced to one year in prison, which he served in Miami County and Jefferson County Jail. After his release during the turn of the century, Walker jointly owned the Union Hotel in Steubenville with Weldy and managed the Opera House, a movie theater nearby Cadiz.

As host to opera, live drama, vaudeville, and minstrel shows at the Opera House, Walker became a respected businessman and patented inventions that improved film reels when nickelodeons were popularized. In 1902, the brothers explored ideas of black nationalism as editors for The Equator, though no copies exist today as evidence. Walker expanded upon his works about race theory by publishing the book Our Home Colony (1908). Regarded as “the most learned book a professional athlete ever wrote,” Our Home Colony shared Walker's thesis on the victimization of the Black race and a proposal for Blacks to emigrate back to Africa.

Ednah died on May 26, 1920. Widowed again, Walker sold the Opera House and managed the Temple Theater in Cleveland with Weldy. On May 11, 1924, Walker died of lobar pneumonia at 67. His body was buried at Union Cemetery-Beatty Park next to his first wife. Although Jackie Robinson is commonly associated with being the first black to play major league baseball, Walker held the honor among baseball enthusiasts for decades. In 2007, researcher Pete Morris discovered that another ball player, former slave William Edward White, actually played a single game for the Providence Grays five years before Walker debuted for the Blue Stockings. Despite these findings, baseball historians still credit Walker as the first in the major leagues to play openly as a black man.