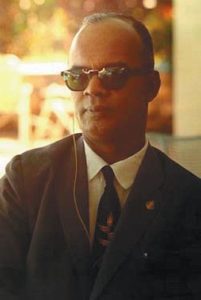

Eric E. Williams

*Eric Williams was born on this date in 1911. He was an Afro Caribbean author, politician, and activist.

Eric Eustace Williams was born in Trinidad. His father, Thomas Henry Williams, was a minor civil servant. Eliza Frances Boissiere's mother was a descendant of the mixed French Creole elite and had African and French ancestry. He attended the Tranquillity Boys' Intermediate Government School and Queen's Royal College in Port of Spain, where he excelled. He won an island scholarship in 1932, which allowed him to attend St. Catherine's Society, Oxford (later renamed St. Catherine's College). In 1935, he received a first-class honors degree and ranked first among history graduates that year.

He also represented the university in football. In 1938, he went on to obtain his doctorate. His doctoral thesis was titled The Economic Aspects of the Abolition of the Slave Trade and West Indian Slavery and was published as Capitalism and Slavery in 1944. It attacked the idea that moral and humanitarian motives were in the success of the British abolitionist movement. It was also a critique of the established British historiography on the West Indies. His debate owed much to the influence of C. L. R. James.

Williams's position about abolitionism went far beyond this decline thesis. He argued that the slave-based Atlantic economy's new economic and social interest created in the 18th century generated new pro-free trade and anti-slavery political interests. This evangelical anti-slavery and self-emancipation of slave rebels moved the Haitian Revolution of 1792-1804 to the Jamaica Christmas Rebellion of 1831 and ended slavery in the 1830s.

In 1939, Williams joined the Political Science department at Howard University. In 1943, he organized a conference about the "economic future of the Caribbean." He argued that small islands of the West Indies would be vulnerable to domination by the former colonial powers if these islands became independent states; Williams advocated for a West Indian Federation as a solution to post-colonial dependence.

In 1944, Williams was appointed to the Anglo-American Caribbean Commission. In 1948 he returned to Trinidad as the Commission's Deputy Chairman of the Caribbean Research Council. He delivered a series of educational lectures there, for which he became famous. In 1955 after disagreements between Williams and the Commission, the Commission elected not to renew his contract.

Until this time, his lectures were under the auspices of the Political Movement, a Teachers Education and Cultural Association branch. In the 1940s, this group was an alternative to the official teachers' union. In January 1956, he inaugurated his political party, the People's National Movement (PNM), which would take Trinidad and Tobago into independence in 1962 and dominate its post-colonial politics. The PNM party strove to separate itself from the transitory political assemblages, which had thus far been the norm in Trinidadian politics.

In elections held eight months later, on September 24, the Peoples National Movement won 13 of the 24 elected seats in the Legislative Council, defeating 6 of the 16 incumbents running for re-election. Although the PNM did not secure a majority in the 31-member Legislative Council, he convinced the Secretary of State for the Colonies to allow him to name the five appointed members of the council. Williams was thus elected Chief Minister and was also able to get all seven of his ministers elected. This gave him a clear majority in the Legislative Council.

After the Second World War, most political parties in the various territories aligned themselves into two Federal political parties – the West Indies Federal Labor Party and the Democratic Labor Party (DLP).

The DLP victory in the 1958 Federal Elections and a subsequent poor showing by the PNM in the 1959 County Council Elections soured Williams on the Federation. Williams declared that "one from ten leaves naught" in a famous speech. Following the adoption of a resolution to that effect by the PNM General Council in January 1962, Williams withdrew Trinidad and Tobago from the West Indies Federation. This led the British government to dissolve the Federation.

The 1961 elections gave the PNM 20 of the 30 seats. This two-thirds majority allowed them to draft the Independence Constitution without input from the DLP. Trinidad and Tobago became independent on August 31, 1962, 25 days after Jamaica. In addition to being prime minister, Williams was also Minister of Finance from 1957 to 1961 and from 1966 to 1971.

Black Power Between 1968 and 1970, the Black Power movement gained strength in Trinidad and Tobago. The leadership was within the Guild of Undergraduates at the University of the West Indies St. Augustine Campus. Williams countered with a broadcast entitled "I am for Black Power" in response to the challenge. He introduced a 5% levy to reduce unemployment and established the first locally-owned commercial bank. However, this intervention had little impact on the protests.

On April 3, 1970, a protester was killed by the police. Williams proclaimed a State of Emergency on April 21 and arrested 15 Black Power leaders in response to this. Williams made three additional speeches in which he sought to identify himself with the aims of the Black Power movement. He reshuffled his cabinet and removed three ministers (including two White members) and three senators. He also proposed a Public Order Bill curtailing civil liberties to control protest marches. The Bill was withdrawn after public opposition. Attorney General Karl Hudson-Phillips offered to resign over the failure of the Bill, but Williams refused his resignation.

Eric Williams died in office on March 29, 1981, at 69. A period of national mourning in Trinidad and Tobago from March 30 to April 17, 1981, followed. Often called the "Father of the Nation," Williams remains one of the most significant leaders in modern Trinidad and Tobago history.

Academic contributions

Williams specialized in the study of slavery. His impact on that field of study has proved of lasting significance. As Barbara Solow and Stanley Engerman put it in the preface to a compilation of essays on Williams based on a commemorative symposium in Italy in 1984, Williams "defined the study of Caribbean history, and its writing affected the course of Caribbean history. Scholars may disagree on his ideas, but they remain the starting point of discussion. Any conference on British capitalism and Caribbean slavery is on Eric Williams." In addition to Capitalism and Slavery,

Williams produced several other scholarly works focused on the Caribbean. Two published long after he abandoned his academic career for public life are of particular significance: British Historians and the West Indies and From Columbus to Castro. Williams sent one of 73 Apollo 11 Goodwill Messages to NASA for the historic first lunar landing in 1969. The message still rests on the lunar surface today. He wrote, in part: "It is our earnest hope for mankind that while we gain the moon, we shall not lose the world."

The Eric Williams Memorial Collection (EWMC) at the University of the West Indies in Trinidad and Tobago was inaugurated in 1998 by former US Secretary of State Colin Powell. In 1999, to the World Register. The Collection consists of some 7,000 volumes and correspondence, speeches, manuscripts, historical writings, research notes, conference documents, and a collection of reports. The Museum contains a wealth of dynamic memorabilia of the period and copies of the seven translations of Williams' major work, Capitalism and Slavery (into Russian, Chinese, and Japanese [1968, 2004] among them, and a Korean translation was released in 2006).

Photographs depicting various aspects of his life and contribution to the development of Trinidad and Tobago complete this vibrant archive, as does a three-dimensional re-creation of Williams' study. In 2011, to mark the centenary of Williams' birth, Mariel Brown directed the documentary film Inward Hunger: The Story of Eric Williams, scripted by Alake Pilgrim.