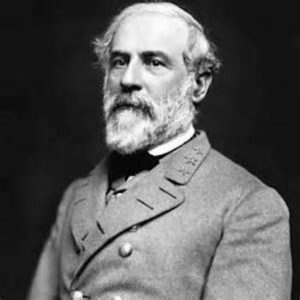

Robert E. Lee

*Robert E. Lee was born on this date in 1807. He was a white-American soldier known for commanding the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia in the American Civil War from 1862 until his surrender in 1865.

Robert Edward Lee was born at Stratford Hall Plantation in Westmoreland County, Virginia, the son of Major General Henry Lee III, Governor of Virginia, and his second wife, Anne Hill Carter. One of Lee's great-grandparents, Henry Lee I, was a prominent Virginian colonist of English descent. Lee's family is one of Virginia's first families (FFV), originally arriving in Virginia from England in the early 1600s with the arrival of Richard Lee I, Esq., from the county of Shropshire. His mother grew up at Shirley Plantation, one of the most elegant homes in Virginia. Lee's father, a tobacco planter, suffered severe financial reverses from failed investments.

In 1857, his father-in-law George Washington Parke Custis, died, creating a serious crisis when Lee took on the burden of executing the will. Custis's will encompassed vast landholdings and hundreds of slaves balanced against massive debts and required Custis's former slaves "to be emancipated by my executors in such manner as to my executors may seem most expedient and proper, the said emancipation to be accomplished in not exceeding five years from the time of my decease." The estate was in disarray, and the plantations had been poorly managed and were losing money.

Lee tried to hire an overseer to handle the plantation in his absence, writing to his cousin, "I wish to get an energetic, honest farmer, who while he will be considerate & kind to the Negroes, will be firm & make them do their duty." But Lee failed to find a man for the job and had to take a two-year leave of absence from the army to run the plantation himself. He found the experience frustrating since many of the slaves had been given to understand that they were to be made free as soon as Custis died, and he protested angrily at the delay.

In May 1858, Lee wrote to his son Rooney, "I have had some trouble with some of the people. Reuben, Parks & Edward, in the beginning of the previous week, rebelled against my authority—refused to obey my orders, & said they were as free as I was, etc., etc. I succeeded in capturing them & lodging them in jail. They resisted till overpowered & called upon the other people to rescue them." Less than two months after they were sent to the Alexandria jail, Lee decided to remove these three men and three female house slaves from Arlington and sent them under lock and key to the slave trader William Overton Winston in Richmond. The latter was instructed to keep them in jail until he could find "good & responsible" slaveholders to work them until the end of the five years.

In 1859, three Arlington slaves, Wesley Norris, his sister Mary, and a cousin, escaped for the North but were captured a few miles from the Pennsylvania border and forced to return to Arlington. On June 24, 1859, the anti-slavery newspaper New York Daily Tribune published two anonymous letters (dated June 19, 1859, and June 21, 1859), each claiming to have heard that Lee had them whipped. Each went so far as to claim that the overseer refused to whip the woman but that Lee took the whip and flogged her personally. Lee privately wrote to his son Custis "The N. Y. Tribune has attacked me for my treatment of your grandfather's slaves, but I shall not reply. He has left me an unpleasant legacy."

Wesley Norris spoke out about the incident after the war in an 1866 interview printed in an abolitionist newspaper, the National Anti-Slavery Standard. Norris stated that after they had been captured and forced to return to Arlington, Lee told them, "he would teach us a lesson we would not soon forget." According to Norris, Lee then had the three of them firmly tied to posts by the overseer and ordered them whipped with fifty lashes for the men and twenty for Mary Norris. Norris claimed that Lee encouraged the whipping and that when the overseer refused to do it, they called the county constable to do it instead.

Unlike the anonymous letter writers, he does not state that Lee himself personally whipped any of the slaves. According to Norris, Lee "frequently enjoined [Constable] Williams to 'lay it on well,' an injunction which he did not fail to heed; not satisfied with simply lacerating our naked flesh, Gen. Lee then ordered the overseer to wash our backs with brine, which was done thoroughly." Lee's agent then sent the Norris men to work on the railroads in Richmond and Alabama. Wesley Norris gained freedom in January 1863 by slipping through the Confederate lines near Richmond to Union-controlled territory. Lee freed the other Custis slaves after the end of the five years in the winter of 1862, filing the deed of manumission on December 29, 1862.

The debate that Lee had always somehow opposed slavery helped maintain his stature as a symbol of Southern honor and national reconciliation. Freeman's analysis places Lee's attitude toward slavery and abolition in a historical context: This [opinion] was the prevailing view among most religious whites of Lee's class in the Border States. They believed that slavery existed because God willed it, and they thought it would end when God so ruled. The time and the means were not theirs to decide, conscious though they were of the ill effects of Negro slavery on both races. Lee shared these convictions of his neighbors without having come in contact with the worst evils of African bondage.

He spent no considerable time in any state south of Virginia from the day he left Fort Pulaski in 1831 until he went to Texas in 1856. All his reflective years had passed in the North or the Border States. He had never been among the Blacks on a cotton or rice plantation. At Arlington, the servants had been notoriously indolent, their master's master. Lee, in short, was only acquainted with slavery at its best, and he judged it accordingly. At the same time, he was under no illusion regarding the aims of the Abolitionists or the effect of their agitation.

Another source cited by defenders and critics is Lee's December 27, 1856 letter to his wife: “In this enlightened age, there are few I believe, but what will acknowledge, that slavery as an institution, is a moral & political evil in any Country. It is useless to expatiate on its disadvantages. I think it, however, a greater evil to the white man than to the black race, & while my feelings are strongly enlisted in behalf of the latter, my sympathies are more strong for the former. The blacks are immeasurably better off here than in Africa, morally, socially & physically. The painful discipline they are undergoing is necessary for their instruction as a race, & I hope will prepare & lead them to better things. How long their subjugation may be necessary is known & ordered by a wise Merciful Providence.”

In 1859, John Brown led a band of 21 abolitionists who seized the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, in October 1859, hoping to incite a slave rebellion. President James Buchanan gave Lee command of detachments of militia, soldiers, and United States Marines, to suppress the uprising and arrest its leaders. By the time Lee arrived that night, the militia on the site had surrounded Brown and his hostages. At dawn, Brown refused the demand for surrender. Lee attacked, and Brown and his followers were captured after three minutes of fighting. Lee's summary report of the episode shows Lee believed it "was the attempt of a fanatic or madman." Lee said Brown achieved "temporary success" by creating panic and confusion and "magnifying" the number of participants involved in the raid. In 1860, Lt. Col. Robert E. Lee relieved Major Heintzelman at Fort Brown, and the Mexican authorities offered to restrain "their citizens from making predatory descents upon the territory and people of Texas...this was the last active operation of the Cortina War".

When Texas seceded from the Union in February 1861, General David E. Twiggs surrendered all the American forces (about 4,000 men, including Lee, and commander of the Department of Texas) to the Texans. Twiggs immediately resigned from the U. S. Army and was made a Confederate general. Lee went back to Washington and was appointed Colonel of the First Regiment of Cavalry in March 1861. The new President, Abraham Lincoln, signed Lee’s colonelcy. Three weeks after his promotion, Colonel Lee was offered a senior command (with the rank of Major General) in the expanding Army to fight the Southern States that had left the Union. Fort Mason, Texas, was Lee's last command with the United States Army.

In the aftermath of the Texas secession, other evidence in favor of the claim that Lee opposed slavery included his direct statements and his actions before and during the war, including Lee's support of the work by his wife and her mother to liberate slaves and fund their move to Liberia, the success of his wife and daughter in setting up an illegal school for slaves on the Arlington plantation, the freeing of Custis' slaves in 1862, and, as the Confederacy's position in the war became desperate, his petitioning slaveholders in 1864–65 to allow slaves to volunteer for the Army with manumission offered as a reward for outstanding service. However, despite his stated opinions, Lee's troops under his command were allowed to actively raid settlements during major operations like the 1863 invasion of Pennsylvania to capture Free Blacks for enslavement freely.

In December 1864, Lee was shown a letter by Louisiana Senator Edward Sparrow, written by General St. John R. Liddell, which noted Lee would be hard-pressed in the interior of Virginia by spring and the need to consider Patrick Cleburne's plan to emancipate the slaves and put all men in the army who were willing to join. Lee was said to have agreed on all points and desired to get black soldiers, saying, "He could make soldiers out of any human being that had arms and legs."

As the possibility of a war between the states became realistic, Lee privately ridiculed the Confederacy in letters in early 1861, denouncing secession as a "revolution" and a betrayal of the efforts of the founders. Writing to his son William Fitzhugh, Lee stated, "I can anticipate no greater calamity for the country than a dissolution of the Union." While he was not opposed in principle to secession, Lee wanted all peaceful ways of resolving the differences between North and South, such as the Crittenden Compromise, to be tried first, and was one of the few to foresee a long and difficult war. The commanding general of the Union Army, Winfield Scott, told Lincoln he wanted Lee for top command. Lee accepted a promotion to colonel on March 28.

He had earlier been asked by one of his lieutenants if he intended to fight for the Confederacy or the Union, to which Lee replied, "I shall never bear arms against the Union, but it may be necessary for me to carry a musket in the defense of my native state, Virginia, in which case I shall not prove recreant to my duty." Meanwhile, Lee ignored an offer of command from the Confederate States of America. After Lincoln's call for troops to put down the rebellion, it was obvious that Virginia would quickly secede. On April 18, Presidential advisor Francis P. Blair offered Lee a role as major general to command the defense of Washington.

He replied: “Mr. Blair, I look upon secession as anarchy. If I owned the four million slaves in the South, I would sacrifice them all to the Union, but how can I draw my sword upon Virginia, my native state?” Lee resigned from the U.S. Army on April 20 and took up command of the Virginia state forces on April 23. His daughter Mary Custis was the only one among those close to Lee who favored secession, and his wife Mary Anna especially favored the Union, so his decision astounded them. While Lee's immediate family followed him to the Confederacy, others, such as cousins and fellow officers Samuel Phillips and John Fitzgerald, remained loyal to the Union, as did 40% of all Virginian officers.

Since the end of the Civil War, it has often been suggested Lee was, in some sense, opposed to slavery. In the period following the war, Lee became a central figure in the Lost Cause interpretation of the war. Lee was not arrested or punished, but he lost the right to vote and some property. He supported President Johnson's plan of Reconstruction but joined with Democrats in opposing the Radical Republicans who demanded punitive measures against the South. He distrusted its commitment to the abolition of slavery and the region's loyalty to the United States. His support for civil rights for all, as well as a system of free public schools for blacks, was moderate.

He directly opposed allowing blacks to vote, stating: "My own opinion is that, at this time, they [black Southerners] cannot vote intelligently, and that giving them the vote would lead to a great deal of demagoguism, and lead to embarrassments in various ways.” President Grant invited him to the White House in 1869, and he went. Nationally he became an icon of reconciliation between the North and South and the reintegration of former Confederates into the national fabric. On September 28, 1870, Lee suffered a stroke. He died two weeks later, on October 12, 1870, in Lexington, Virginia, from the effects of pneumonia. Lee's prewar family home, the Custis-Lee Mansion, was seized by Union forces during the war and turned into Arlington National Cemetery. The family was compensated in 1883.