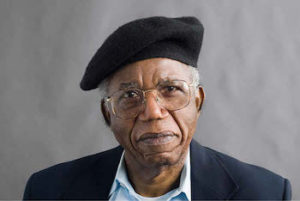

Chinua Achebe

*Chinua Achebe was born on this date in 1930. He was a Black African Author and literary activist.

Albert Chinualumogu Achebe was born in Ogidi, an Ibo village in Nigeria. His father became a Christian and worked as a missionary teacher in various parts of Nigeria before returning to the village. As a student, Achebe immersed himself in Western literature. At the University College of Ibadan, whose professors were Europeans, he read Shakespeare, Milton, Defoe, Swift, Wordsworth, Coleridge, Keats, and Tennyson.

But the turning point in his education was the required reading of "Mister Johnson," a 1939 novel set in Nigeria and written by an Anglo-Irishman, Joyce Cary. The protagonist is a docile Nigerian whose British master shoots and kills him. Like reviewers in the Western press, Achebe’s white professors praised it as one of the best novels ever written about Africa. But he and his classmates responded with “exasperation at this bumbling idiot of a character,” which he wrote.

He soon joined a generation of West African writers who, in the 1950s, realized that Western literature was holding the continent captive. A fellow Nigerian, Amos Tutuola, opened the floodgates with his 1952 novel, “The Palm-Wine Drinkard.” After graduating from college in 1953, Achebe moved to London, where he worked for the British Broadcasting Corporation while writing stories.

In London, he wrote “Things Fall Apart” in longhand. After returning to Nigeria to revise the manuscript, he mailed the only existing copy to a London typing service, which promptly misplaced it; it was discovered only months later. Publishers initially passed on the manuscript, doubting that African fiction would sell until an adviser at the Heinemann publishing house seized on it as a work of brilliance. He wrote his second novel, “No Longer at Ease,” in 1960 and his third novel, “Arrow of God,” in 1964.

In 1966, the Nigerian Civil War, also known as the Biafran War, shattered Achebe’s hopes for a more promising postcolonial future and profoundly affected his literary output. In 1967, the Ibo seceded from Nigeria, declaring the southeastern region the independent Republic of Biafra. The civil war began in earnest, raging through 1970 until government troops invaded and crushed the secessionists. Achebe’s fourth novel, “A Man of the People,” published in early 1966, had predicted this course of events with such accuracy that the military government in Lagos decided he must have been a conspirator in the first coup.

Achebe fled, settling in Britain with his wife, Christiana; their two sons, Ikechukwu and Chidi; and two daughters, Chinelo and Nwando. After the civil war, Achebe returned to Nigeria for two years before accepting faculty posts in the 1970s at the University of Massachusetts and the University of Connecticut. He returned home in 1979 to teach English at the University of Nigeria.

The Civil War was the theme of many of his writings. Among the most prominent was a book of poetry, “Beware Soul Brother” (1971), which won the Commonwealth Poetry Prize, and a short-story collection, "Girls at War,” which appeared in 1972. In 1988, Achebe finally published his fifth novel, “Anthills of the Savannah.” Achebe was in a car accident outside Lagos; he received medical treatment in London and moved to the United States, taking a teaching post at Bard College in the Hudson River valley, where he remained until 2009.

He received the Man Booker International Prize for lifetime achievement in 2007. He published “There Was a Country: A Personal History of Biafra.” The return of civilian, democratic rule to Nigeria in 1999 prompted Mr. Achebe to visit for the first time in almost a decade. He met the newly elected president, Olusegun Obasanjo, and cautiously praised him as the best possible leader “at this time.” He also traveled to his native village, Ogidi. He said that Achebe returned to the United States, but his heart remained in his homeland.

In his writing and teaching, Achebe sought to reclaim the continent from Western literature, which he felt had reduced it to an alien, barbaric, and frightening land devoid of art and culture. He took particular exception to "Heart of Darkness," the novel by Joseph Conrad, whom he thought “a thoroughgoing racist.” In 2008, he said in an interview with The Associated Press, “I grew up among very eloquent elders,” “In the village, or even in the church, which my father made sure we attended, there were eloquent speakers.” He said that eloquence was not reflected in Western books about Africa, but he understood the challenge of rectifying the portrayal.

Achebe once said, “You know that it’s going to be a battle to turn it around, to say to people, ‘That’s not the way my people respond in this situation, by unintelligible grunts, and so on; they would speak, and it is that speech that I knew I wanted to be written down.” Chinua Achebe, the Nigerian author and towering man of letters whose internationally acclaimed fiction helped to revive African literature and to rewrite the story of a continent that Western voices had long told, died on March 22, 2013, in Boston. He was 82.