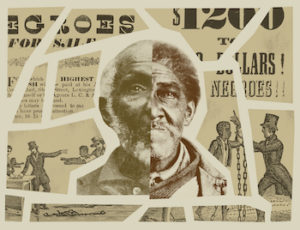

Anthony Johnson (likeness)

*The birth of Anthony Johnson is celebrated on this date in 1606. He was an African slave and farmer and one of the first Black property owners in colonial America. He was a tobacco farmer in Maryland and had his right to legally own a slave recognized by the Virginia courts.

There is no information about his childhood (we chose this articles' date because it coincides with when Virginia became an American colony). In the early 1620s, slave traders captured him in Angola, named him Antonio, and sold him into the Atlantic slave trade. He was brought to Virginia in 1621 aboard the James. The Virginia Muster (census) of 1624 lists his name as "Antonio not given," recorded as "a Negro" in the "notes" column. Historians have some dispute as to whether this was Antonio later known as Anthony Johnson, as the census lists several "Antonio’s." This one is considered the most likely. Antonio was converted to the Catholic religion. After arriving in Virginia, Johnson was sold as an indentured servant to a white planter named Bennet to work on his Virginia tobacco farm.

(Slave laws were not passed until 1661 in Virginia; before that date, Africans were not officially considered to be slaves). The work required remained brutal, the description was merely a different word. Such workers typically worked under a limited indenture contract for four to seven years to pay off their place in the middle passage, room, board, lodging, and freedom dues. In the early colonial years, most Africans in the Thirteen Colonies were held under such contracts of limited indentured servitude. Except for those indentured for life, they were released after a contracted period. Those who managed to survive their period of indenture would receive land and equipment after their contracts expired or were bought out. Many white laborers in this period also came to the colony as indentured servants. After 1661, slave laws meant the slave had no contract and was a slave for life. Antonio was almost killed in the Indian massacre of 1622 when Bennet's plantation was attacked. The Powhatan Native Americans were attempting to evict the colonists. They raided the settlement where Johnson worked on Good Friday and killed 52 of the 57 men present. In 1623, a black woman named Mary arrived aboard the ship Margaret and was brought to work on the same plantation as Antonio. Antonio and Mary married and lived together for more than forty years.

Conclusion of indentured servitude

Sometime after 1635, he and his wife concluded the terms of their indentured servitude. Antonio changed his name to Anthony Johnson. He first entered the legal record as an unindentured man when he purchased a calf in 1647. On July 24, 1651, he acquired 250 acres (100 ha) of land. Johnson was granted a large plot of farmland by the colonial government after he paid off his indentured contract by his labor. This was under the headright system by buying the contracts of five indentured servants, one of whom was his son Richard Johnson. The headright system worked in such a way that if a man were to bring indentured servants over to America (in this particular case, Johnson brought the five servants), he was owed 50 acres a "head", or servant. The land was located on the Great Naswattock Creek, which flowed into the Pungoteague River in Northampton County, Virginia.

With his indentured servants, Johnson ran his tobacco farm. One of those servants, John Casor, would later become one of the first Black African men to be declared indentured for life. Before the Antebellum South, in this early period, about 20% of free Black Virginians owned their own homes. In 1652, "an unfortunate fire" caused "great losses" for the family, and Johnson applied to the courts for tax relief. The court reduced the family's taxes and on February 28, 1652, exempted his wife Mary and their two daughters from paying taxes at all "during their natural lives." At that time, taxes were levied on people, not property. Under the 1645 Virginia taxation act, "all negro men and women and all other men from the age of 16 to 60 shall be judged tithable." It is unclear from the records why the Johnson women were exempted, but the change gave them the same social standing as white women, who were not taxed. During the case, the justices noted that Anthony and Mary "have lived Inhabitants in Virginia (above thirty years)" and had been respected for their "hard labor and known service".

By the 1650s, Anthony and Mary Johnson were farming 250 acres in Northampton County while their two sons owned a total of 550 acres. They had the services of five indentured servants (four white and one black). In 1653, John Casor, a black indentured servant whose contract Johnson appeared to have bought in the early 1640s, approached Captain Goldsmith, claiming his indenture had expired seven years earlier and that he was being held illegally by Johnson. A neighbor, Robert Parker, intervened and persuaded Johnson to free Casor. Parker offered Casor work, and he signed a term of indenture to the planter. Johnson sued Parker in the Northampton Court in 1654 for the return of Casor. The court initially found in favor of Parker, but Johnson appealed. In 1655, the court reversed its ruling. Finding that Anthony Johnson still "owned" John Casor, the court ordered that he be returned with the court dues paid by Robert Parker.

This was the first instance of a judicial determination in the Thirteen Colonies holding that a person who had committed no crime could be held in servitude for life. Though Casor was the first person who was declared a slave in a civil case, there were both black and white indentured servants sentenced to lifetime servitude before him. Many historians describe indentured servant John Punch as the first documented slave (or slave for life) in America, as punishment for escaping his captors in 1640. Punch was required to "serve his said master or his assigns for the time of his natural Life here or elsewhere". The Punch case was significant because it established the disparity between his sentence as a negro and that of the two European indentured servants who escaped with him (one described as Dutch and one as a Scotsman). It is the first documented case in Virginia of an African sentenced to lifetime servitude. It is considered one of the first legal cases to make a racial distinction between black and white indentured servants.

Significance of Casor lawsuit

The Casor lawsuit demonstrated the culture and mentality of planters in the mid-17th century. Individuals made assumptions about the society of Northampton County and its place in it. According to historians T.H. Breen and Stephen Innes, Casor believed he could form a stronger relationship with Robert Parker than Anthony Johnson had formed over the years. Casor considered the dispute to be a matter of patron-client relationship, and this wrongful assumption resulted in his losing his case in court and having the ruling against him. Johnson knew that the local justices shared his basic belief in the sanctity of property. The judge sided with Johnson, although in future legal issues, race played a larger role. The Casor lawsuit was an example of how difficult it was for Africans who were indentured servants to prevent being reduced to slavery. Most Africans could not read and had almost no knowledge of the English language.

Planters found it easy to force them into slavery by refusing to acknowledge the completion of their indentured contracts. This is what happened in Johnson v. Parker. Although two white planters confirmed that Casor had completed his indentured contract with Johnson, the court still ruled in Johnson's favor. In 1657, Johnson’s white neighbor, Edmund Scarborough, forged a letter in which Johnson acknowledged a debt. Johnson did not contest the case. Johnson was illiterate and could not have written the letter; nevertheless, the court awarded Scarborough 100 acres (40 ha) of Johnson’s land to pay off his alleged "debt".

The Johnson story is one of many of the first cases of how Blacks were victims of land redistribution and theft. In 1662 the Virginia Colony passed a law that children in the colony were born with the social status of their mother. This meant that the children of slave women were born into slavery, even if their fathers were free, European, Christian, and white. This was a reversal of English common law, which held that the children of English subjects took the status of their father. The Virginian colonial government expressed the opinion that since Africans were not Christians, common law could and did not apply to them. Anthony Johnson moved his family to Somerset County, Maryland, where he negotiated a lease on a 300-acre (120 ha) plot of land for ninety-nine years. He developed the property as a tobacco farm, which he named Tories Vineyards. Mary survived, and in 1672 she bequeathed a cow to each of her grandsons.

Research indicates that when Johnson died in 1670, his plantation was given to a white colonist, not to Johnson's children. A judge had ruled that he was "not a citizen of the colony" because he was black. In 1677, Anthony and Mary’s grandson, John Jr., purchased a 44-acre (18-hectare) farm which he named Angola. John Jr. died without leaving an heir, however. By 1730, the Johnson family had vanished from the historical records.