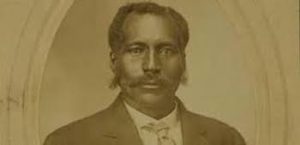

Antony P. Crawford

*The birth of Anthony Crawford is celebrated on this date in 1865. He was a Black businessman.

From Abbeville, South Carolina, Anthony P. Crawford’s mother, and father were Thomas Crawford and Phoebe Williams. His grandfather Charles Crawford, born in 1780, survived the Middle Passage. He had three brothers and three sisters, Sanders Crawford, Andrew Crawford, Jackson Crawford, Fanny Downs, Sina Aiken, and Rebecca Richey. His family was owned by Ben and Rebecca Crawford, white Americans in Abbeville, South Carolina, before emancipation. He walked 14 miles roundtrip to and from school daily and proved quite a scholar. When Anthony finished school, he was a laborer for Ben Crawford until Thomas Crawford, Anthony’s father, died in 1893 and deeded some land to Anthony, the only nine siblings able to sign his name.

Andy (as he was known) had 13 children, all of whom lived on his land with their spouses and children. He built a school on his land for the Black children of Abbeville and also held an office with the Masons of South Carolina. He was for 19 years secretary and chief financial prop of Chapel AME Church. In October of 1894, he was Assistant Marshall of a grand parade in which some 1,500 to 2,000 persons assembled by trades. Black US Congressman George W. Murray was the guest speaker. In August of 1888, the local newspaper reported that he sold three wagons of splendid melons and finds as much money in them as cotton. I

n December of 1904, the Abbeville Medium reports: Anthony P. Crawford, colored, sold a load of splendid corn of his own raising in the city last week. His fat mules, good wagon, and prosperous appearances led us to inquire particularly about his crop. He owns and farms the old Belcher place. He holds in his own right 500 acres of land in three tracts, paid for by his own labor. This year his corn crop was 1000 bushels, of which he sold 250. He made 200 gallons of syrup and 48 bales of cotton. November 26th, he sold $662.08 worth of cotton and has made other sales. He has six horses, 12 head of cattle, 18 hogs, two good wagons, a McCormick rake, and a new top buggy. He also has a good bank account and a family of 13 children.

Crawford became well-respected and was a very successful businessman. He is said to have owned 10 percent of the land owned by Blacks in the county. He had relatively good relationships even with the white citizens of Abbeville, primarily due to his wealth. But he was still a Black man who jeopardized his life with a business dispute with a white man in the Jim Crow south.

On October 21, 1916, Crawford was taking two loads of cotton and a load of seed into Abbeville and had a disagreement over the price of cottonseed with W.D. Barksdale, a white store owner. He was not about to be cheated out of the market price for his harvest of cottonseed. The argument between Crawford and the vendor intensified and moved into the town square, drawing the attention of local residents. After Crawford left the store, one of Barksdale's employees followed him outside and hit him on the head with an ax handle. Crawford called for help, which drew the attention of Sheriff R.M. Burts.

The officer arrested Crawford, most likely for his protection, as a mob of angry whites was already beginning to gather. He paid his bail and was on his way when the angry crowd of whites spotted him. Crawford fought to defend himself, but the crowd stormed the jail, beat Crawford nearly to death, tied him to the back of a buggy, and dragged him to a location nearby where they hung him from a tree while armed whites used his body for target practice.

The paper's headline the next day read "Negro Strung Up and Shot to Pieces." After dark, the county coroner, F.W.R. Nance, took a jury to the fairground and cut down Crawford's mutilated remains. The coroner found Crawford had died "at the hands of parties unknown." After Crawford’s murder, his family was ordered to get out of town. This lynching caused the emigration of over half of the black population of Abbeville to leave as well. Crawford’s family settled in parts of Illinois, Washington, DC, and Philadelphia.

In 2005, the 109th Congress of the United States Senate passed Resolution 39, which was a formal apology to African Americans for Congress's failure to pass any kind of anti-lynching legislation despite over 200 anti-lynching bills having been introduced to Congress at that time. The resolution was issued before the descendants of Anthony Crawford, among other surviving descendants of lynching victims. It marked the first occasion that Congress had apologized to African Americans for any reason. In contrast, Congress had in the past apologized to other ethnic groups (e.g., Japanese-Americans) for the actions of the United States.