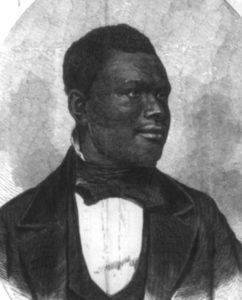

Anthony Burns

*Anthony Burns was born on this date in 1834. He was a Black Preacher and fugitive slave.

Anthony Burns was born enslaved in Stafford County, Virginia. His mother, also enslaved by John Suttle, died shortly after his birth. His mother was a cook for the Suttle family and had 13 children, with him as her youngest. His father was a free man and supervisor for a quarry in Virginia, who later died from stone dust inhalation.

After John Suttle died, his widowed wife took over his estate and sold his older siblings to prevent bankruptcy. When he was 6, Mrs. Suttle died. Her property, including him, was inherited by her eldest son, Charles F. Suttle. Burns looked after his niece to be available for labor and stayed at the House of Horton, where his sister lived and worked. Here, the children taught Burns the alphabet in exchange for small services. At age 7, Burns was hired out to three single women to work for $15 a year.

At 8, Burns went to work for $25 a year and was offered a chance to learn. In this job, the children taught Burns how to spell through their spelling worksheets from school; he worked in this capacity for two years and left due to poor treatment. William Brent next leased him. During this time, Burns learned about freedom up North. He began dreaming of his escape and freedom. Burns entered the hiring ground to find a new master under a lease hire arrangement. He was 12–13 years old then and did not want to remain enslaved.

Some 2–3 months into his service, Anthony mangled his hand in the wheel after Foote turned it on without warning. While recovering from the injury to his hand, Anthony had a religious awakening that superseded other experiences. Simultaneously, Millerism came to his small county in Virginia, and Burns was excited by the religious fervor spread. However, after Burns returned to his employment, Suttle permitted him to get baptized. Two years later, he preached to a group of church members exclusively to slave assemblies. Additionally, Burns performed marriages and funerals for enslaved persons as a preacher. He finished his year of service and was hired by a new master in Falmouth, Virginia, near his church.

He was loaned to a merchant for six months, was treated horribly, and refused to remain with the lessee after his year of service was completed. Burns moved to Fredericksburg, Virginia the next year, where he worked under a tavern keeper. Shortly later, Suttle hired William Brent, who moved Burns to Richmond, Virginia, at the end of his year of service. There, Brent hired him out to be his brother-in-law. With his knowledge, he set up a makeshift school to teach slaves of all ages how to read and write, a secret from their masters in Richmond. At the end of his year of service with Brent's brother-in-law, Burns was employed by Millspaugh.

Millspaugh quickly set Anthony out into the city to work small jobs and earn money for him. In his job search, Burns learned how to escape from the sailors and freemen where he worked. In one of their biweekly meetings, he gave Millspaugh $25 as his earnings that month, and after being presented with such a large sum, his master required Burns to visit him daily. Anthony refused and devised a plan to escape. One morning in early February 1854, Anthony boarded the vessel that would take him to the North. The vessel reached Boston in early March, and Burns immediately began seeking new employment.

At first, he found a job as a cook on a ship. Next, Burns found employment under Collin Pitts, a man of color, in a clothing store for one month of freedom in this capacity before being arrested. While in Boston, Burns sent a letter to his enslaved brother in Richmond, whose owner discovered the letter and conveyed the news of Burns' escape to Suttle. Suttle went to a courthouse where the judge ruled that Suttle had enough proof that he owned Burns and could issue a warrant for his arrest under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.

The warrant was issued on May 24, 1854. Burns went before Judge Edward G. Loring to stand trial. On that same day, Asa O. Butman, an infamous slave hunter, was charged with executing the warrant. By the first day of the trial, the prosecutors had kept the trial hidden from the public. Suttle asked Anthony to write a letter proving him a good master. Still, Leonard Grimes, a Black Boston clergyman and abolitionist, had Burns destroy the letter.

The final examination began on May 29, 1854. Armed soldiers lined the courthouse windows and prevented all officials and citizens from entering the courtroom. In Loring's final decision, he admitted that he thought the Fugitive Slave Act was a disgrace, but his job was to uphold the law. Loring stated that Suttle produced sufficient evidence to prove the fugitive slave Suttle described matched Burns's appearance; thus, he ruled in favor of Suttle. It has been estimated that the government's cost of capturing and conducting Burns through the trial was over $40,000 (equivalent to $1,152,000 in 2020).

After leaving Massachusetts, Burns spent four months in a Richmond jail without contact with other slaves. In November, Suttle sold Burns to David McDaniel for $905, and McDaniel brought Burns to his plantation in Rocky Mount, North Carolina. Burns worked as McDaniel's coachman and stable keeper, a relatively light workload compared to other slaves on the plantations. Instead of lodging with the other slaves, Burns received an office and ate meals in his master's house. In addition to Burns's level of care as a slave, Burns attended church twice while serving four months under McDaniel. Burns even held illegal religious meetings for his fellow slaves. During these months of enslavement, Burns failed to notify his Northern friends of his location in the South.

One afternoon, Burns drove his mistress to a neighbor's house. Burns was seen as the slave who had caused a commotion with his trial in the North. A young lady overheard the neighbor recalling the story to her social circle, including Reverend Stockwell, who told Leonard Grimes. Stockwell wrote to McDaniel to begin negotiations for Burns's purchase, and McDaniel responded, saying he would sell Burns for $1300. In the two weeks before they left for Baltimore to meet McDaniel and Burns, Grimes collected sufficient funds for Burns's purchase while Stockwell covered the expenses for their journey.

McDaniel knew he was going against public sentiment in North Carolina by selling Burns to the Northerners, so he swore Anthony to secrecy. In Baltimore, Burns and McDaniel met Grimes at Barnum's Hotel. They arrived two hours after Grimes and immediately began negotiations. The payment was exchanged and freed him. Upon leaving the hotel, Grimes and Burns met Stockwell at the entrance. He accompanied the men to the train station. Burns spent his first night as a free man in Philadelphia.

Burns reached Boston in early March and met a public celebration of his freedom. Eventually, Burns enrolled at Oberlin College with a scholarship. He entered a seminary in Cincinnati to continue religious studies. After briefly preaching in Indianapolis in 1860, Burns moved to St. Catharine's, Ontario, Canada, in 1860 to accept a call from Zion Baptist Church. Thousands of Africans had migrated to Canada as refugees from slavery in the antebellum years, establishing communities in Ontario. Anthony Burns died from tuberculosis on July 17, 1862.