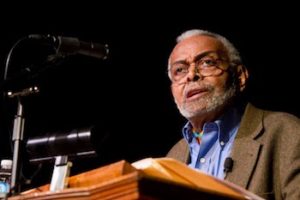

Amiri Baraka

Amiri Baraka was born on this date in 1934. He was a Black writer, probably best known as a playwright and poet.

Born Everett LeRoi Jones in Newark, NJ, his father was a postman and forklift operator, and his mother, Anna Lois Russ, was a social worker. Jones studied philosophy and religion at Rutgers, Columbia, and Howard Universities, though he earned no degree. After these experiences, Jones joined the US Air Force for three years. An anonymous letter to his commanding officer accusing him of being a communist led to the discovery of Soviet writings. Jones was put on gardening duty and given a dishonorable discharge for violating his oath of duty.

From there, Jones went to New York's Greenwich Village in 1957. He began working in a record warehouse, which fueled his interest in Black music and brought him into contact with writers such as Nat Hentoff, Martin Williams, and Allen Ginsberg. These individuals' influences on Jones's early career affected his Beat-era poetry. One year later, he founded Totem Press. Jones also spent time in Fidel Castro's Cuba in the early 1960s.

Jones married Hettie Cohen in 1960, a white-Jewish woman he had been working with while writing for Yugen magazine. By 1964, he had achieved fame in the New York literary community. He wrote critically acclaimed off-Broadway plays, beginning with "The Dutchman" in 1964, followed by "The Slave" in 1965. Jones also recorded and performed with the free jazz group the New York Art Quartet in this era.

After the murder of Malcolm X in 1965, Jones dropped his Beat identity. He left Greenwich Village for Harlem and changed his name to Imamu Amiri Baraka, embracing the new Black liberation ideology. Amiri Baraka has undergone many changes in his life and professional career as a writer and poet. In 1965 Baraka divorced Cohen, abandoning her and their two children. In her autobiography, "How I Became Hettie Jones," Cohen would later write that Baraka had physically abused her and the children for years.

Malcolm X's murder also marks the point in Baraka's career where charges of racism, homophobia, and anti-Semitism were made against him. "I don't see anything wrong with hating white people," Baraka told a U.S. News and World Report writer. One of Baraka's popular Harlem street performances in 1965 involved a Black valet murdering white victims. From 1965 to 1974, Baraka devoted himself to the Black Nationalist cause and the Congress of Afrikan Peoples.

After moving to Harlem, Baraka and several other associates began The Black Arts Repertory Theater (BART). Its goal was to "create an art that would be a weapon in the Black Liberation Movement." BART was a short-lived endeavor, lasting only one year. Funding came largely from then-President Lyndon Johnson's Great Society programs. When Jones' senior aid, Sargent Shriver, visited BART for a public relations campaign, Jones refused admission to the premises, telling the "Jew Shriver" to "go /*#* himself." In the 1960s and early 1970s, Baraka penned what many see as his most anti-Semitic works: After the murder of Martin Luther King, Jr., in 1968, Baraka was jailed during the riots that broke out in Newark. Baraka then became heavily involved in local electoral politics.

He was a key member in the campaign to elect a black mayor (Kenneth Gibson), drawing people like Jesse Jackson and Harry Belafonte to Newark. Baraka's efforts helped Gibson win the election. Baraka commented on the election's revolutionary implications: "We will nationalize the city's institutions," he wrote before the vote, "as if it were liberated territory in Zimbabwe or Angola." Unfortunately, Gibson was later thrown out of office on fraud and conspiracy charges. Around 1974, Baraka abandoned Black Nationalism, Marxism, and Third Worldism, dropping the Muslim Imamu from his name.

In 1980, Baraka claimed to have overcome his hostility toward Jews. He wrote in "Confessions of a Former Anti-Semite," that he should be understood as an anti-Zionist. "Zionism is a form of racism. It is a political ideology that hides behind the Jewish religion and the Jewish people while performing its negative tasks for imperialism." As for Jews, he made it clear that the ones he approved of were those who weren't too Jewish. He praised "the movement among middle-class Jews to become straight-up Americans" and said, "shedding their 'Jewishness' represents a progressive trend." When Rutgers University denied him tenure in 1990, he criticized the tenure committee, denouncing its members as "Ivy League Goebbels," "white supremacists," and "powerful Klansmen," whose "intellectual presence makes a stink across the campus like the corpses of rotting Nazis." Baraka had a small, though memorable role in the 1998 film Bullworth.

In the fall of 2001, Baraka composed a poem called "Somebody Blew Up America." The poem was read publicly and circulated, and later became the source of controversy when he was named Poet Laureate of New Jersey. The poem was written about the 9/11/01 attacks. Among other criticisms, some people interpreted sections of the poem as saying that the Israeli government had prior knowledge of the attack or even was responsible.

Following the controversy, Baraka stated that the poem was not anti-Semitic and stated, "I do believe, as I stated about England, Germany, France, Russia, that the Israeli government, certainly its security force, SHABAK knew about the attack in advance." It must be noted that many critics have argued that the various 9/11 conspiracy claims regarding Jews or Israel are baseless. Governor James McGreevey called for Baraka's resignation as poet laureate and, when he refused, asked the state legislature to abolish the post, which it did in 2003.

Amiri Baraka died on January 9, 2014, at Beth Israel Medical Center in Newark, New Jersey,

The African American Desk Reference

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture

Copyright 1999 The Stonesong Press Inc. and

The New York Public Library, John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Pub.

ISBN 0-471-23924-0