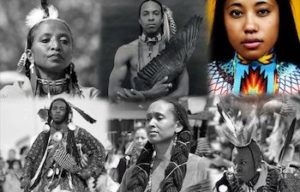

*On August 3, 1990, President George H. W. Bush declared November as Native American Indian Heritage Month. To further affirm this community, we are sharing a brief article on the intersectionality of both African and Native Americans. From the beginning of U. S. history, American Native populations and Africans had a historical relationship of both cooperation and confrontation.

Europeans first enslaved Indians, introducing Africans to the Americas shortly after. Nicolas de Ovando, Governor of Hispaniola, first mentioned African and Indian interaction in a report circa 1503. Indians who escaped generally knew the surrounding areas avoided capture and returned to help free enslaved Africans. Europeans feared an Indian/African alliance. The first slave rebellion occurred in Hispaniola in 1522, while the first on future United States soil (North Carolina) occurred in 1526. Both rebellions were organized and executed by coalitions of Africans and Indians.

Europeans feared communities of escaped Africans, known as Maroons or quilombos, in frontier areas. The largest of these communities, the "Republic of Palmore's," originated in the 1600s and, at its peak, had a population of approximately 11,000. This community, composed primarily of Africans but including Indians, contained three villages, spiritual gathering places, and shops and operated under its legal system. Its army repelled European military attacks until 1694.

The Lumbee are a distinct Tri-racial Native American ethnic group that includes African people. They have lived in southeastern North Carolina since about 1625. Numbering about 50,000, they are primarily located in Robeson County, NC. Also, the Shinnecock is a federally recognized tribe of historically Algonquian-speaking Native Americans based at the eastern end of Long Island, New York. With African roots, and despite having documented history since the 1700s, their roots go even further back.

White reaction to such communities was extreme despite their limited numbers. Europeans sought to separate the two peoples and, if possible, mutually hostile. They taught Africans to fight Natives and bribed Indians to hunt escaped Africans, promising lucrative rewards. Natives who captured escaped Africans received 35 deerskins in Virginia or three blankets and a musket in the Carolinas. Further sowing division, Whites introduced African slavery into the Five Civilized Nations in the United States. The Intersectionality between Africans and Natives is further born out in Joseph Louis Cook, who fought against the British in the Revolutionary War.

The U. S. government ended slavery among Indians by 1776. From pre-Revolutionary times to the American Civil War, the government negotiated treaties with Indian tribes that included promises by the Indians to return escaped slaves. However, while harboring many slaves, they returned none. The most powerful African-Native alliance linked escaped Blacks who had settled in Florida and Seminoles (a word that means "runaway") who fled the Creek Federation. They fought whites for years to preserve their heritage; Fort Okeechobee is an example. The Africans taught the Natives rice cultivation, and the groups formed an agricultural and military alliance.

In 1816, a U. S. soldier reported that prosperous plantations existed for fifty miles along the banks of the Apalachicola River. The African-Seminole forces repeatedly repelled U. S. slaveholders' posses and the U. S. Army. The Second Seminole War resulted in 1,600 dead and cost over $40 million. The purchase of Florida from Spain was the U. S. government's attempt to eliminate it as a refuge for runaways. Before the American Civil War, many Native American nations on the eastern seaboard of the United States became biracial communities.

Blacks were victims of the Indian Removal Act of 1830. By 1860, the Five Civilized Nations in the Indian Territory consisted of 18 percent Africans. The Seminoles appointed six Black Seminoles members to its governing council. After the American Civil War, the Buffalo Soldiers, six regiments of Black U. S. Army troops, helped to end Native resistance to U. S. control after the War. The most significant African-Native American was John Horse, a Black Seminole Chief, a master marksman, and a diplomat in Florida and Oklahoma. By the time of the American Civil War, the Black Seminole Chief was in Mexico and Texas.

Horse negotiated a treaty with the U. S. government in 1870. On July 4th of that year, when his Seminole nation crossed into Texas, it was a historic moment: an African people had arrived together on this soil under the command of their ruling monarch, Chief John Horse. Today, many African Americans can trace their ancestry in part to a Native American tribe.

African American and Native American History

Princeton Public Library

65 Witherspoon Street

Princeton, NJ 08542

609-924-9529