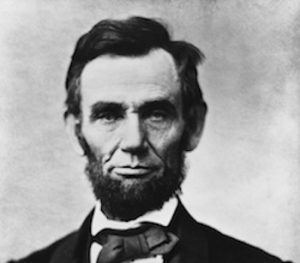

Abraham Lincoln

*Abraham Lincoln was born on this date in 1809. He was a white-American politician and lawyer and the 16th President of the United States.

Lincoln was born in Hodgenville, Kentucky, in western Kentucky and Indiana. Largely self-educated, he became a lawyer in Illinois, a Whig Party leader, and was elected to the Illinois House of Representatives, where he served for eight years. He was elected to the United States House of Representatives in 1846. There, Lincoln promoted rapid modernization of the economy through banks, tariffs, and railroads. Because he had originally agreed not to run for a second term in Congress and because his opposition to the Mexican–American War was unpopular among Illinois voters, Lincoln returned to Springfield and resumed his law practice. Reentering politics in 1854, he became a leader in building the new Republican Party, which had a statewide majority in Illinois. In 1858, while participating in a series of debates with his opponent, Democrat Stephen A. Douglas, Lincoln spoke out against the expansion of slavery. Still, he lost the U.S. Senate race to Douglas.

In 1860, Lincoln secured the Republican Party presidential nomination as a moderate from a swing state. Though he gained very little support in the slaveholding states of the South, he swept the North and was elected president in 1860. Lincoln's victory prompted seven southern slave states to form the Confederate States of America before he moved into the White House. No compromise or reconciliation was found regarding slavery and secession. Lincoln was not a slave owner; his wife, Mary Todd, was the daughter of a Kentucky slave owner.

On April 12, 1861, the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter inspired the North to rally behind the Union enthusiastically. As the leader of the moderate faction of the Republican Party, Lincoln confronted Radical Republicans, who demanded harsher treatment of the South, War Democrats, who called for more compromise, anti-war Democrats (called Copperheads), who despised him; and irreconcilable secessionists who plotted his assassination. As President, he rejected two geographically limited emancipation attempts by Major General John C. Fremont in August 1861 and by Major General David Hunter in May 1862 because it was not within each man's power, and it would upset the Border States loyal to the Union. Politically, Lincoln fought back by pitting his opponents against each other, carefully planned political patronage, and appealing to the American people with his powers of oratory.

His Gettysburg Address became an iconic endorsement of the principles of nationalism, republicanism, equal rights, liberty, and democracy. Lincoln initially concentrated on the military and political dimensions of the war. His primary goal was to reunite the nation. He suspended habeas corpus, leading to the ex-parte Merryman decision, and he averted potential British intervention in the war by defusing the Trent Affair in late 1861. Lincoln closely supervised the war effort, especially the selection of top generals, including his most successful general, Ulysses S. Grant. He also made major decisions on Union war strategy, including a naval blockade that shut down the South's normal trade, moving to control Kentucky and Tennessee, and using gunboats to gain control of the southern river system. Lincoln tried repeatedly to capture the Confederate capital at Richmond; each time a general failed, Lincoln substituted another until Grant finally succeeded.

As president during those years, Lincoln oversaw the Dakota War of 1862. This was also known as the Sioux Uprising, Dakota Uprising, the Sioux Outbreak of 1862, the Dakota Conflict, the U.S.–Dakota War of 1862, or Little Crow's War. This was an armed conflict between the United States and several bands of the Dakota tribes. Throughout the late 1850s, treaty violations by the United States and late or unfair annuity payments by Indian agents caused hunger and suffering among the Dakota. It began on August 17, 1862, along the Minnesota River in southwest Minnesota. That day, one young Dakota with a hunting party of three others killed five settlers while on a hunting expedition. That night, a council of Dakota attacked settlements throughout the Minnesota River valley to drive whites out of the area. Over the next several months, continued battles pitting the Dakota against settlers and, later, the United States Army ended with the surrender of most of the Dakota bands. By late December 1862, soldiers had taken captive more than a thousand Dakota who were interned in Minnesota jails. One ally of the Dakota was Joseph Godfrey, a Minnesota escaped Black slave. After trials and sentencing, 38 Dakota were hanged on December 26, 1862, in the largest one-day execution in American history. In April 1863, the rest of the Dakota were expelled from Minnesota to Nebraska and South Dakota. The United States Congress also abolished their reservations.

During Lincoln’s term in office, the American Civil War was America’s bloodiest war and perhaps its most moral, constitutional, and political crisis. In governing the United States through it he preserved the Union, paved the way for the abolition of slavery, strengthened the federal government, and modernized the economy. Lincoln understood that the Constitution limited the Federal government's power to end slavery, which before 1865 committed the issue to individual states. He argued before and during his election that the eventual extinction of slavery would result from preventing its expansion into new U.S. territory. At the beginning of the war, he also sought to persuade the states to accept compensated emancipation in return for their prohibition of slavery. Lincoln believed that curtailing slavery in these ways would economically expunge it, as envisioned on paper by the Founding Fathers under the Constitution.

The ending of slavery was a demonstration of the President’s executive war powers, not a moral response. The Southern states used slaves to support their armies and manage the home front so more men could go off to fight. They also used them to leverage political representation in Washington, D.C. That being said, in a display of his political savvy, Lincoln justified the Emancipation Proclamation as a “fit and necessary war measure” to cripple the Confederacy’s use of slaves in the war effort. Lincoln also declared that the Proclamation would be enforced under his power as Commander-in-Chief and that the freedom of the slaves would be maintained by the “Executive government of the United States.” On June 19, 1862, endorsed by Lincoln, Congress passed an act banning slavery on all federal territory.

In July, the Confiscation Act of 1862 was passed, which set up court procedures that could free the slaves of anyone convicted of aiding the rebellion. Although Lincoln believed it was not within Congress's power to free the slaves within the states, he approved the bill in deference to the legislature. He felt the Commander-in-Chief, using the Constitution's war powers granted to the president, could only take such action, and Lincoln was planning to take that action. Privately, Lincoln concluded at this point that the slave base of the Confederacy had to be eliminated. Although he said he wished all men could be free, Lincoln stated that the primary goal of his actions as the U.S. president was to preserve the Union.

The Emancipation Proclamation, issued on September 22, 1862, and put into effect on January 1, 1863, declared free the slaves in 10 states not then under Union control, with exemptions specified for areas already under Union control in two states. Lincoln spent the next 100 days preparing the army and the nation for emancipation, while Democrats rallied their voters in the 1862 off-year elections by warning of the threat freed slaves posed to northern whites. Once the abolition of slavery in the rebel states became a military objective, as Union armies advanced south, more slaves were liberated until all three million in Confederate territory were freed. Lincoln's comment on the signing of the Proclamation was: "I never, in my life, felt more certain that I was doing right than I do in signing this paper." Lincoln continued earlier plans to set up colonies for the newly freed slaves for some time. He favored colonization in the Emancipation Proclamation, but all attempts at such a massive undertaking failed.

A few days after Emancipation was announced, 13 Republican governors met at the War Governors' Conference; they supported the president's Proclamation but suggested the removal of General George B. McClellan as commander of the Union Army. Enlisting former slaves in the military was official government policy after the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation. By the spring of 1863, Lincoln was ready to recruit black troops in more than token numbers. By the end of 1863, General Lorenzo Thomas had recruited 20 regiments of blacks from the Mississippi Valley at Lincoln's direction. Frederick Douglass once observed of Lincoln: "In his company, I was never reminded of my humble origin, or of my unpopular color."

As the war progressed, his complex moves toward ending slavery included using the U.S. Army to protect escaped slaves, encouraging the border states to outlaw slavery, and pushing through Congress the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. Being politically involved with power issues in each state, Lincoln reached out to the War Democrats and managed his re-election campaign in the 1864 presidential election. Anticipating the war's conclusion, Lincoln pushed a moderate view of Reconstruction, seeking to reunite the nation speedily through a policy of generous reconciliation in the face of lingering and bitter divisiveness. On April 14, 1865, five days after Confederate commanding general Robert E. Lee surrendered, John Wilkes Booth, a Confederate sympathizer, assassinated Lincoln. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton launched a manhunt for Booth, and 12 days later, on April 26, Booth was fatally shot by Union Army soldier Boston Corbett. Lincoln has been consistently thought of as among the greatest U.S. presidents.